Chaplain Michael Zoosman does a different type of research

His research reveals a family tragedy – and heroism

Science perpetually builds on itself, working on the knowledge and discoveries of the past. For example, we would likely never have had laparoscopic surgery if the utility of a sterile operating environment hadn't been discovered in the generations before.

This too was the case for Clinical Center Chaplain Michael Zoosman, in his personal research to uncover his family's history. Zoosman, a former prison and psychiatric hospital chaplain, works as a multi-faith hospital chaplain in the Clinical Center's Spiritual Care Department, providing resources and support for patients and their families during their hospital stay.

Zoosman had heard stories from his grandmother of his family's escape from Poland during World War II, but the tales were fragmented. His aunt had attempted to document the specifics of the family's history and eventually that torch was passed to him.

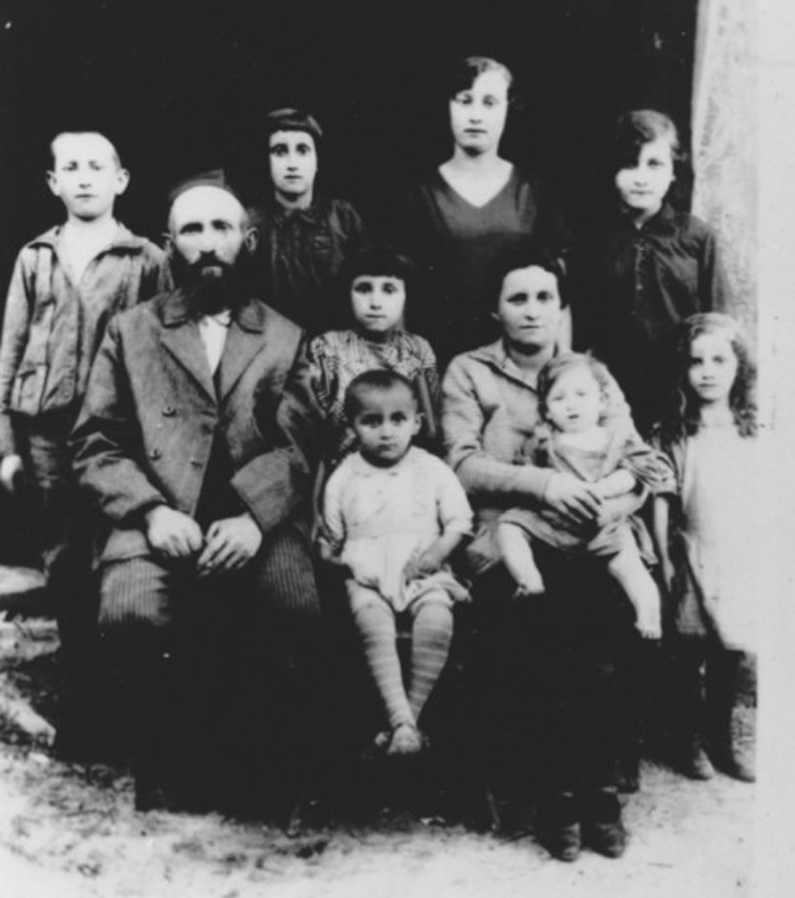

Zoosman knew that his grandmother, Clara, was part of the Spektor family, a family of 10 who lived on a small farm in Volyn, Poland (which falls in present day Ukraine). The five sisters and three brothers grew up modestly, selling produce for income. But, it wasn't until he proactively recorded his grandmother and his aunt's accounts – using a karaoke machine – that the story came into focus.

In 1941, when Poland was occupied by Nazis, the Spektor family who were still living in Volyn were forced to migrate to a Jewish ghetto nearby called Kozin, also in (then) Poland. The eldest sister, Faiga, was living with her husband and son further away in a town called Operand.

By the summer of 1942, they were no longer safe in the ghetto, and most of the family fled when it was rumored that Nazis were coming to kill the occupants of Kozin. Their mother stayed behind with their youngest brother, and the police found them hiding in a closet and killed them both. Their father and another son stayed with an acquaintance but the man's son – a police officer – shot and killed them. The last son hid in various stables until he was hunted and murdered in the street in a place called Bashaba.

The four unmarried sisters managed to stay on the run long enough to eventually connect with a Polish Catholic farmer, a man the family knew only as Mr. Cegielski, who harbored them at great personal peril.

He hid them first in straw stacks and eventually in a small bunker that he allowed the girls to build for themselves out of sticks, roots and straw. He brought them each a potato and a bottle of water when he could manage it. Local Nazi sympathizers came to pillage Cegielski's home and ultimately murdered him for harboring Jews. The four sisters managed to stay hidden until Cegielski's son let them know of his father's death.

The sisters decided their best chance of survival was to split up and use aliases and false documents to hide their identities. Despite their efforts, one sister was killed when it was discovered she was Jewish. After the war ended, the remaining sisters reconnected with three of them eventually moving to the United States and one emigrating to Buenos Aires, Argentina.

As Zoosman documented his grandmother's memories and conducted research, the process continued to yield dead ends. The names and locations from the stories were hazy and resources for tracking information were sparse. He wrote an extensive thesis for Brandeis University on the history that his grandmother dictated orally, but verifying the information was grueling and often unfruitful.

Frustrated, Zoosman posted his thesis to his social network at large. He was not expecting anything to come from it, but since his research was at a standstill he decided to take a chance.

Assistance came from an unlikely source – an old friend of Zoosman's from high school read his thesis and was able to locate a small museum in Markowa, Poland: The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II. Even without Cegielski's first name, the museum had enough contextual evidence to make a match. The Polish Catholic farmer who had saved the lives of the four Spektor sisters was named Michal Cegielski

With the identity of the man who had saved the Spektor sisters uncovered, Zoosman's 100-year-old grandmother applied for Cegielski to be recognized by the Yad Vashem museum in Israel. Yad Vashem translates to "a memorial and a name" in Hebrew and serves as a museum and memorial to victims of the holocaust. On Dec. 8, 2021, the request was granted, and Mr. Cegielski was acknowledged by the museum as "Hasidei Ummot ha-Olam," a Hebrew term meaning "Righteous Members of the Nations of the World."

In a twist of fate, 40 years after Michal Cegielski sheltered Zoosman's relatives, Cegielski's great-grandchildren are working to support Ukrainians who are fleeing the current conflict and into Poland.

Zoosman gave a detailed account at an event hosted by the CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center. CANDLES was founded by a survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp and is a museum dedicated to education about the Holocaust.

Watch and read more

Watch Michael Zoosman give the full CANDLES presentation: The Survival of the Spektor Sisters: A Testament to the Righteous or you can read his thesis.

- Daniel Silber