Experts from NIH and the Middle East cure patient with rare tumor

In November 2015, Jumana, a teenage patient, arrived at the NIH seeking a cure for a rare disease that made her bones so fragile and muscles so weak that she was confined to her bed, barely able to lift her legs. Earlier this year, after a medical collaboration by NIH researchers and others around the world, Jumana was cured and is able to walk again.

The patient, who traveled nearly 6,000 miles from her home in the Palestinian territories to the Clinical Center, had a disease called tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO). TIO is caused by a rare endocrine tumor that secretes FGF23, a hormone that regulates phosphate absorption and active vitamin D production. In high levels, as is seen in TIO, it causes low blood phosphate levels that leads to muscle weakness, bone pain and fractures.

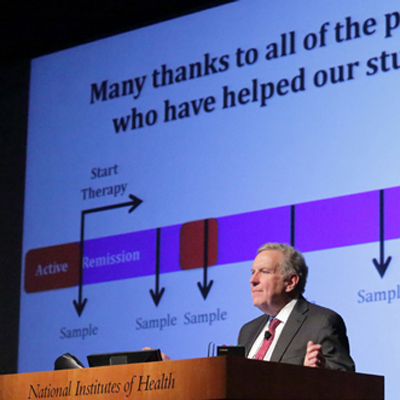

There are only a few places in the world with expertise in diagnosing and treating TIO. When clinicians in Israel diagnosed the condition in this patient, but couldn't find the tumor, they called Dr. Michael Collins, chief of the Skeletal Clinical Studies Unit for the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

Collins and his team took on the challenge of finding the tumor.

Other disorders caused by FGF23 disruption are the result of genetic glitches and usually reveal themselves early in life. The symptoms of TIO typically begin between the ages of 30 and 40, which means that when a teenager shows up with TIO, it can often be confused with the genetic form. The only way to make a sure diagnosis of whether high FGF23 is the result of a genetic glitch or acquired, which is what TIO would be considered, is to find the tumor. That, according to Dr. Collins, is akin to finding the proverbial needle in a haystack.

"Most of the tumors that cause TIO are about the size of a pea," says Dr. Collins, "and they can be in bone or soft tissue anywhere in the body — from head to toe. The fact that they can be anywhere and that they're small compounds is the difficulty in finding them."

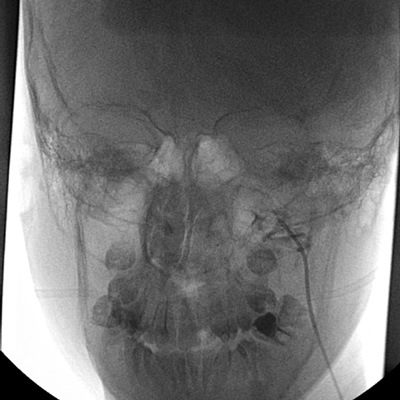

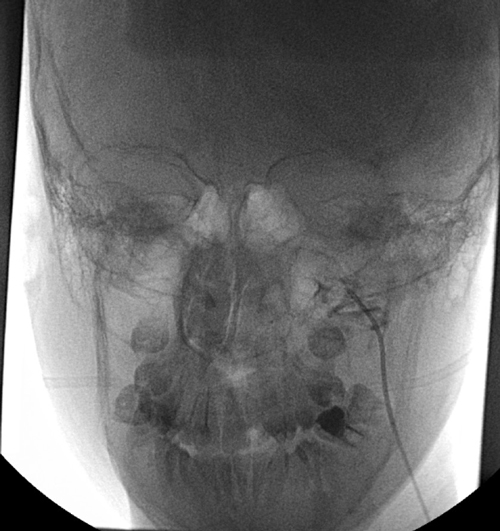

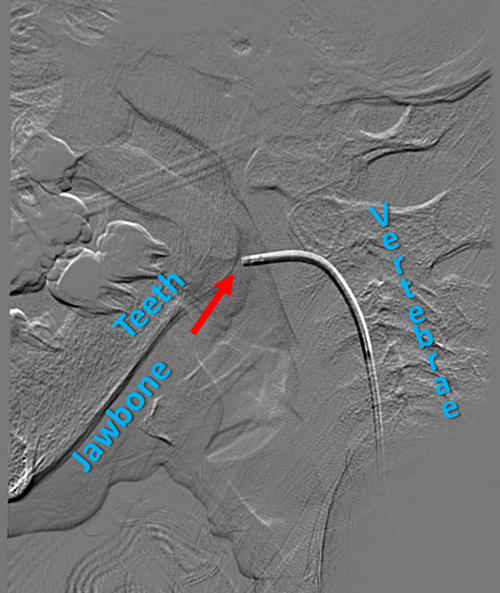

Collins and his team, however, had developed a procedure under a NIDCR clinical trial that used a technique known as selective venous sampling (SVS) to measure levels of FGF23 in the small veins surrounding a potential TIO-causing tumor. As one gets close to the tumor, the levels of FGF23 in the veins gets higher, confirming that the suspected lesion is the tumor. Functional and anatomical imaging studies could turn up likely spots, but only SVS could make a positive identification.

According to Collins, there are only a few places in the world where venous sampling can be done for TIO.

"One of the limiting factors," he says, "is the need for an interventional radiologist who is skillful enough to guide a catheter about the size of a thread through the tiny veins that surround the tumor. Luckily, NIH has Dr. Richard Chang [from the NIH Clinical Center Radiology and Imaging Sciences Department] who can do that."

Once SVS had positively identified a tumor in Jumana's upper jaw bone, Collins and his clinical team began to explore what needed to happen next. Surgery would remove a large portion of her jaw, and a palatal obturator, a device used to cover the surgical opening to allow eating and drinking while the area healed, would have to be inserted.

After surgery, she would also require several months of reconstruction to rebuild her jaw, physical therapy to help her walk again and endocrinological follow-up to make sure that her levels of FGF23 return to normal.

Swiftly, Collins pulled together a multidisciplinary team of experts, centered at NIDCR, to review Jumana's case and its special requirements. Under the direction of Dr. Janice S. Lee, clinical director of NIDCR, Collins arranged a videoconference amongst NIDCR physicians, post-doctoral scholars and other clinicians to analyze the patient's case.

"Sometimes experts for these conferences are pulled in from outside NIH," said Lee. "When Dr. Collins came to us with this case, we already had the videoconferencing capacity so that everyone involved could see the imaging studies, records and whatever else we had to look through."

The review of Jumana's case involved experts around the world, including surgical and medical teams from Haifa and Nablus, the largest city in the Palestinian territories on the West Bank, Dr. John van Aalst, a plastic surgeon from Cincinnati Children's Hospital who already had ties to the region from regularly donating his surgical services to a hospital in Haifa, and additional NIDCR and NIH doctors who had experience with head and neck surgery. Together, the multinational group systematically thought through the entire process to identify areas of expertise and the procedures needed for surgical removal of the tumor and rehabilitation.

During this time, Jumana's family, who had traveled with her to the Clinical Center, explained that they had to get back home. Her father was the sole breadwinner in the family and couldn't afford to stay away from his job much longer. Help was provided to them by the United Palestinian Appeal, a Washington and members of St. Aphraim Syriac Orthodox church.

In January 2016, the family traveled back to Israel, and shortly thereafter a team of fifteen doctors from Israel and the Palestinian territories, including Aalst, performed the 90-minute surgery. Within a week of removing the tumor, Jumana was standing and several weeks after that she was walking again. She periodically sends videos to Collins to show him her progress.

"Once you take out the tumor that causes TIO, you've cured the disease," said Collins. "For patients with TIO and their doctors, it's extremely satisfying. We don't often get the chance to really cure."

For Lee, the case is a gratifying example of NIDCR's global presence.

"What happens around the world, also helps our patients here in the U.S." said Lee. "Our clinical team understands that these diseases have no boundaries; a rare tumor like this can be found anywhere in the world."

Learn more about rare disease research at the NIH Clinical Center and the annual Rare Disease Day at NIH cohosted by the NIH Clinical Center and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.