Department of Transfusion Medicine staff save the life of a patient with rare blood disease

Clinical Center collaborates with partners in Germany to obtain blood

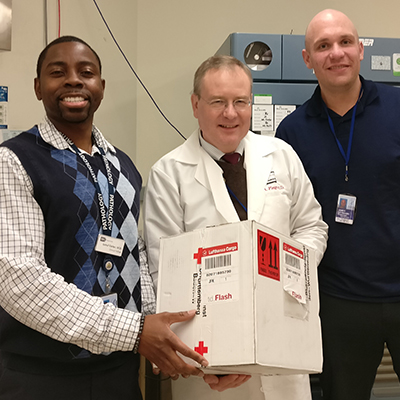

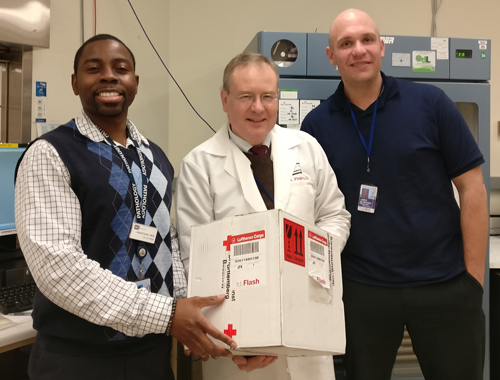

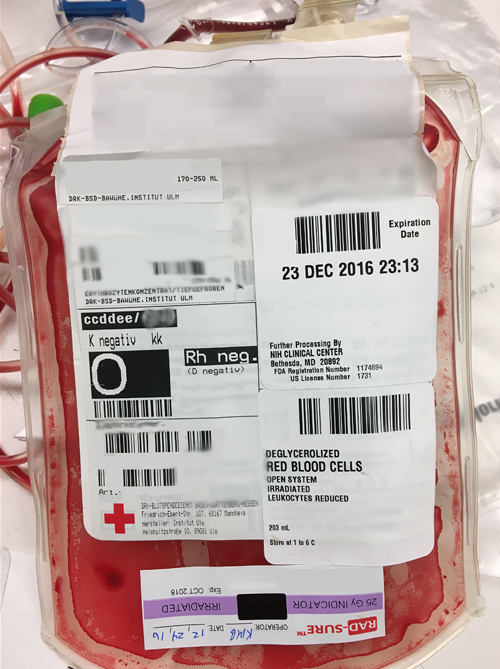

In December 2016, within 24 hours of its departure from a blood donation center in Germany, two units of rare blood arrived at the NIH Clinical Center's Department of Transfusion Medicine.

The unique delivery, containing thawed blood, arrived by international carrier to treat a 59-year-old patient from Canada with a devastating rare blood disease called severe aplastic anemia. Dr. Willy Flegel, chief of the Laboratory Services Section and Dr. Jamal Carter, a clinical fellow with the Department of Transfusion Medicine, received the package and had to act quickly.

In a healthy human, bone marrow produces three types of blood cells needed by the body: red blood cells (to carry oxygen), white blood cells (to fight infection) and platelets (to control bleeding). Severe aplastic anemia can occur when a patients' bone marrow doesn't make enough new blood cells. The most common supportive treatment for severe aplastic anemia is blood transfusion, which is what this patient needed. A search for blood which matches that of the patient is routinely performed at the NIH Blood Bank, and then compatible blood is transfused.

However, in addition to severe aplastic anemia, the patient also had an extremely rare antibody in her blood. Antibodies are proteins that help recognize foreign substances, like bacteria or viruses, and help get rid of them. But, this patient had an antibody that attacked a specific red cell antigen that appears in 99 percent of people's blood.

"The patient's antibody is exceedingly rare. The antibody that her blood has makes it incredibly difficult to find compatible blood," said Carter. "If you transfuse blood that the antibody recognizes [one with the antigen], it will destroy it, and the patient could experience a potentially fatal reaction."

The Canadian facility at which the patient was being treated did not have a match for this rare blood type, so they treated her with blood that had the antigen. The patients' response was poor and she experienced multiple serious adverse reactions to the transfusions. Due to the complicated nature of her care, she was referred to the NIH Clinical Center.

Of severe aplastic anemia, Flegel said, "Patients with this disease depend on the transfusion of blood products for extended periods of time. If there was no blood product to transfuse, then they could die before the definitive treatment takes effect."

Upon her arrival, an evaluation of the NIH blood supply determined blood within NIH was not a suitable match for this patient. Carter and Marina Bueno, a technical specialist in the Immunohematology Reference Laboratory, contacted outside blood donation organizations about the potential of a match for the patient's rare blood type.

Two compatible units were obtained through the American Rare Donor Program [disclaimer] but once that supply was delivered to the patient, the Department of Transfusion Medicine needed more. They had to broaden the search.

Reaching out to international blood bank organizations, Flegel was excited to learn that DRK-Blutspendedienst Ulm [disclaimer]. had units of this rare blood type available. But, getting the blood transferred from Germany to the United States and then transfused to the patient within the time limit set by regulators was challenging.

After conferring with James "Wade" Atkins, supervisor of Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs in the Department of Transfusion Medicine, the NIH team worked on the logistical travel plan alongside the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Customs and Border Control. Blood services in the U.S. and Germany were coordinated by Traci Paige, acting laboratory supervisor, to make the trans-Atlantic blood delivery happen.

In the end, through collaboration and hard work by all involved parties, two units of blood made it to the NIH Clinical Center and were transfused to the patient without any adverse reactions.

Reflecting on the experience, Flegel noted, "This trans-Atlantic collaboration worked out very well, and the many institutions and authorities contributed to ensure the patient's care and safety."

The transfusions supported the patient while she received more definitive treatment for her severe aplastic anemia. The patient's clinical status soon improved dramatically, and she has since stopped requiring regular transfusions.

Learn more about rare disease research at the NIH Clinical Center and the annual Rare Disease Day at NIH cohosted by the NIH Clinical Center and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.